Return to Table of Contents | Proceed to Part V

School Times for End Times

Part IV:

The Social Movements Era of the 1940s to 1990s

Further positioning public schools as sites of struggle

The Social Movements Era is the period from around the end of World War II in 1945 to today. During this era, U.S. society experienced several overlapping and transformational events—the Cold War, the Third Industrial Revolution, the Civil Rights Movement, the Federal Era in Education, and the Conservative Movement—that further positioned public schools as a central site of ideological and political struggle, particularly for Christian Nationalists.[40]

The Cold War and the Third Industrial Revolution

Pop Quiz #6: In what year was “under God” added to the Pledge of Allegiance?

(a) 1934

(b) 1944

(c) 1954

(d) 1964

(e) 1974

Bonus: In what year was “In God We Trust” made the official motto of the United States?

(a) 1936

(b) 1946

(c) 1956

(d) 1966

(e) 1976

Keep reading to see the answer.

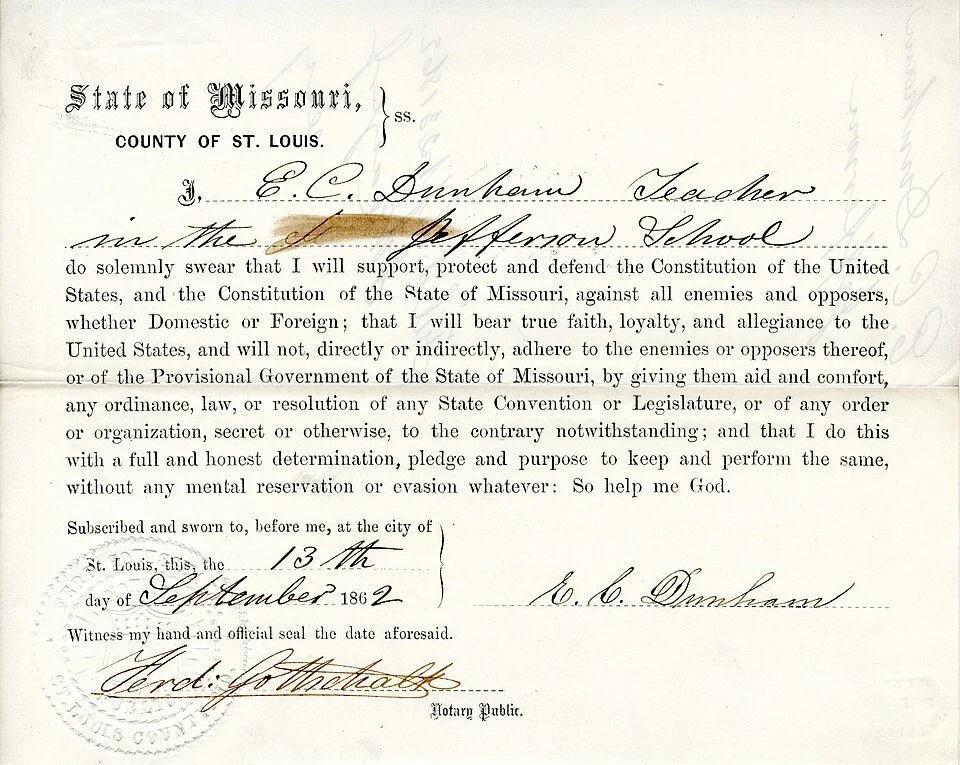

The Cold War, spanning from 1947 (after World War II) to 1991 (the collapse of the Soviet Union), was a period of intensifying tension between, on the one hand, the United States and its allies of capitalist countries (called the Western bloc), and on the other, the Soviet Union and its allies of communist countries (called the Eastern bloc). One of the ideological projects for the United States at this time was not just to elevate American democracy, but also to position a number of things as its antithesis, particularly communism. Examples of such efforts included the “loyalty” (or, subsequently, “security”) tests to weed out communists among public employees, starting in the late 1940s, that would extend to include loyalty oaths for teachers for decades more (although it should be noted that teachers have had to take loyalty oaths previously, including this signed oath of loyalty to the country and the state from the 1860s—see example below). Also in the late 1940s would begin the Lavender Scare that purged the government of thousands of purportedly lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, plus other nonnormative (LGBTQ+) employees or potential employees by claiming that their queerness or “perversion” put them at risk of being traitors—which was a moral panic and legal discrimination that would persist for decades. With the 1950s came a renewed Red Scare, particularly with the McCarthy era witch-hunts of supposed communists.[41]

The American nationalist project overlapped with and even provided cover for the Christian Nationalist project. Examples include in 1954 when Christians (particularly, Catholics) successfully pushed to add the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance by arguing that Christianity is what helped to distinguish and elevate the United States from communist countries. So, too, in 1956 when “In God We Trust” became the official motto of the United States. Starting in the late 1950s, the John Birch Society—viewing the Cold War as a war between good and evil, or between God and ungodliness—led protests targeting schools and school boards for their intertwined failures to stamp out communism and to elevate Christian teachings.[42]

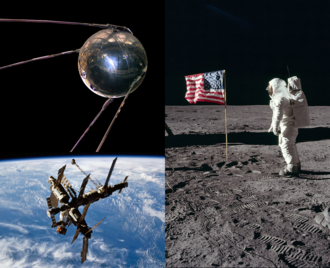

The Cold-War presumption of American superiority would soon be tested, particularly in the Space Race where the Soviet’s 1957 launch of the first outer-space satellite, Sputnik I, gave the United States a crisis in identity and confidence. Attention at the federal level turned to the education system, questioning whether it was falling short of serving our imperialist ambitions and calling for more investment in science and technology as core contributors to American exceptionalism and global dominance, including more investment in school-based instruction in STEM (or, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). In the sciences, one of the main focuses for an enhanced biology curriculum would be evolution.[43]

This technonationalism helped to fuel the Third Industrial Revolution, also known as the Digital Revolution or Information Age, spanning from around the mid-1940s to the 1990s. During this period, due to technological innovations and investments in computing, the economy shifted increasingly from industries centered on traditional manufacturing to those on information technologies. Schools followed suit: in addition to teaching more STEM, schools placed more and more curricular emphasis on computer literacy and would integrate more and more of the education technologies that were (and still are) rapidly emerging in number and form.

Image #1: Loyalty Oath of Teacher E.C. Dunham, Missouri, 1862 (public domain)

Image #2: U.S.S.R.’s Sputnik I and U.S.’s landing on the moon (various, Space Race images, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Image #3: “Keeping Up with Science,” by Shari Weisberg, between 1936-1939, Federal Art Project WPA (public domain)

As happened previously during the First and the Second Industrial Revolutions, the elevating of science and technology raised concerns among some Christians that religion was being further displaced in schools and society by a technonationalism that seemed to be becoming more and more like a secular religion. Some of the most prominent examples of re-Christianization in education during the Cold War and Third Industrial Revolution occurred in the sciences, particularly in opposition to the renewed interest in teaching evolution. Although some Christians continued to call for teaching creationism instead of evolution, what became the more prominent strategy was to call for a curriculum that gave “equal time” or “balanced treatment” to both concepts—on the one hand, evolution science, and on the other, “creation science” or “Intelligent Design.”[44]

Repeatedly, such strategies did not find support in federal courts. In the 1968 Epperson v. Arkansas case, the U.S. Supreme Court held that an Arkansas law that forbade teaching that “mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals” and that strategically avoided explicit mandating of creationism was nonetheless doing so and, therefore, was unconstitutional. So too with the 1987 Edwards v. Aguillard case, in which the Supreme Court held that a Louisiana law (the Balanced Treatment Act)—which required teaching “creation science” if evolutionary science was being taught—was akin to mandating the teaching of creationism, which violated the Establishment Clause. In the 2005 Kitzmiller v Dover Area School District case, a U.S. District Court ruled that the district policy requiring the teaching of “Intelligent Design” was of religious intent, even if not explicitly so, and therefore violated the Establishment Clause.[45]

Re-Christianization was happening in higher education as well with a focus on building a Christian Nationalist base among university students. One example was the creation of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute in 1953 by William F. Buckley, Jr., who criticized higher education as being too secular and socialist. This Institute would go on to train the next generation of conservative leaders that rose to prominence in the 1970s and beyond. Another example was the co-founding of Campus Crusade for Christ (now called, Cru) in 1951 by Bill Bright, which was an interdenominational, evangelical parachurch organization that would seed and support chapters in universities as a way to draw many more young people into Christianity. Cru’s most rapid growth occurred in the 1970s as it coordinated with the youth-energizing Jesus Movement that also helped to significantly expand other campus evangelical parachurch organizations at that time, such as the InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA (founded decades earlier in 1941).[46]

Communism, to American nationalists, was not just anti-American and anti-God, but anti-family as well. For Christian Nationalists, this provided the justification to push an image of the American family that elevated what they considered to have long been at its core, particularly traditional gender roles for men (as the leader in both public and private spaces) and for women (as the homemaker, mother, and wife in obeyance of the husband). In the decades to follow, progressive social movements that aimed to broaden what it meant to be a man or woman—including sexual liberation, feminism, abortion rights, queer rights, trans rights—would prompt Christian Nationalists to double-down on traditional gender roles by making certain aspects more extreme, be they the leaderly and patriarchal roles for men or the domestic and childbearing roles for women. By challenging the identities that lay at the heart of Christian Nationalism, it was not surprising that gender-related social movements were and still are among the most emotionally explosive targets of attacks (as we will see in a moment).[47]

Image: LGBTQ+ advocacy (Rhododendrites, Stonewall Inn with Orlando nightclub shooting memorial during Pride 2016 (50126p), CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Civil Rights Movement and the Federal Era in Education

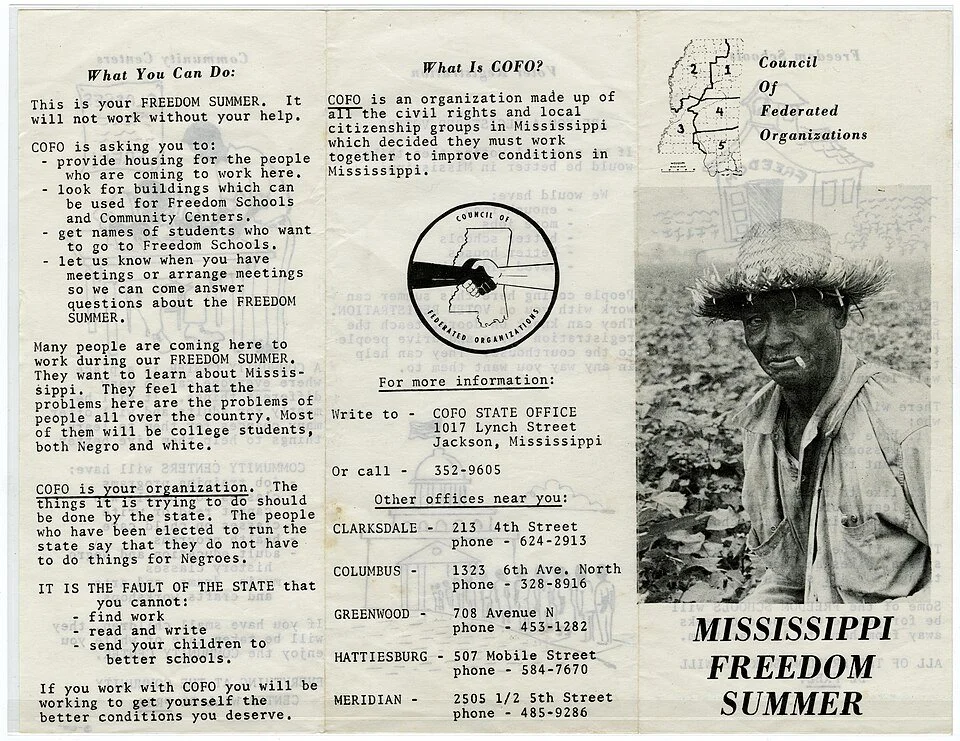

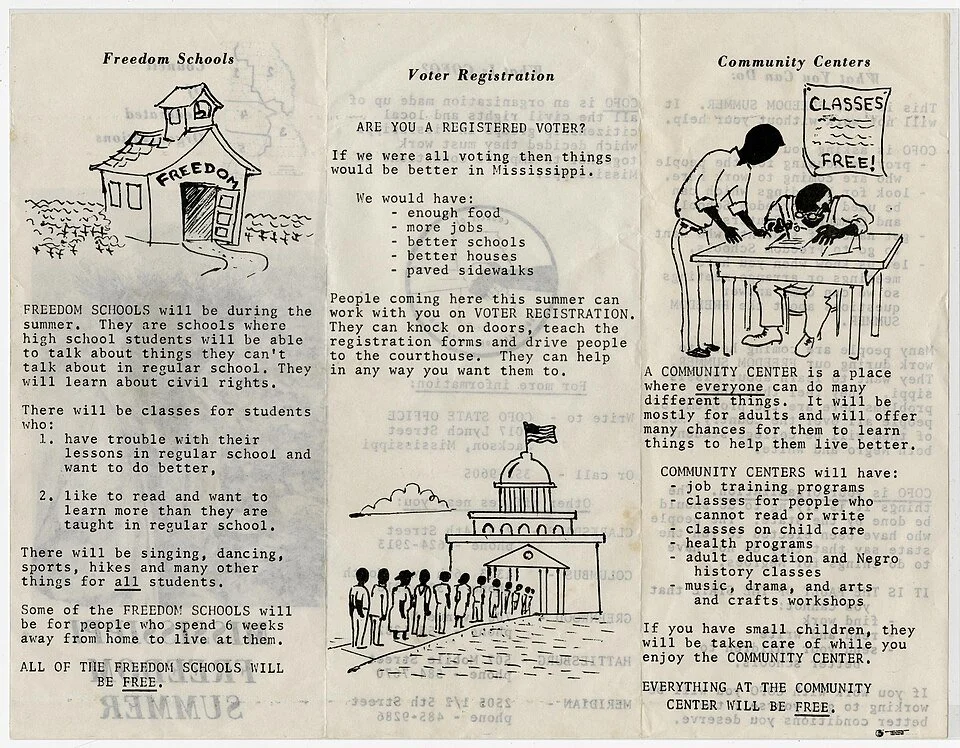

In addition to the Cold War and the Digital Revolution, two other profound societal transformations occurring in this period were the Civil Rights Movement and the Federal Era in Education.[48] Prior to 1954, the federal government played a minimal role in public education, leaving it to state and local governments to oversee schools, which also meant leaving intact a de facto discriminatory schooling system. What forced the federal government to begin to enforce constitutional protections against racial and other forms of discrimination were the Civil Rights Movement and other intersecting social movements, including feminist, anti-war, anti-poverty, anti-colonial, and LGBTQ+ rights movements. Spanning from around the 1940s to 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was a synergy of mass mobilizations, legal struggles, and social and cultural campaigns to counter racial and related discrimination and injustice and to advance human and civil rights in the United States, particularly for Black people but with intersectional analyses and initiatives. Although much of the groundwork was already being laid in the 1940s, one of the events often considered to have brought the Civil Rights Movement to the national stage was the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, in which the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were inherently unequal and that a segregated system violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Among its most widespread initiatives were freedom schools, modeled by the Mississippi Freedom Schools of 1964, that offered free, alternative education, primarily for Black communities, for both youth and adults, in public, private, and church spaces on both academic and political topics with the goal of advancing social and economic justice (see sample flyer below).

Pop Quiz #7: Can you match each Federal Era legislation to the year it was passed? (1964, 1965, 1968, 1972, 1975)

(a) Bilingual Education Act

(b) Civil Rights Act

(c) Education for All Handicapped Children Act

(d) Elementary and Secondary Education Act

(e) Title IX of the Education Amendments

Keep reading to see the answer.

The quarter century that followed Brown was the Federal Era in Education, a period of significant intervention by and influence of the federal government over education through legislation and the courts, concluding in 1979 with legislation to create (or, technically, re-create) the U.S. Department of Education. During this period, civil rights advocacy led to legislation that leveraged federal funding—that is, threatened to withhold federal funds—in order to compel compliance with nondiscrimination laws. Such was the precedent set by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which finally helped to advance desegregation, particularly in the South, soon to be followed by the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 that focused on racial and economic disparities as part of President Johnson’s Great Society and War on Poverty initiatives. Following these was a string of major laws that addressed other, intersected forms of discrimination in public schools, including the Bilingual Education Act of 1968, the Education Amendments of 1972 that included Title IX on sex and gender discrimination, and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (later called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA). Litigation continued throughout this period as well, leading to such landmark Supreme Court decisions as in the 1974 Lau v. Nichols case mandating accommodations for English language learners, and the 1978 Regents of University of California v. Bakke case setting the framework for constitutional affirmative action in university admissions.

In addition to race, the courts were paying attention to questions about religious freedom. Beginning with the 1947 case of Everson v. Board of Education of the Township of Ewing, and continuing well into the 1970s, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a series of decisions that set forth constitutional limits on the majority’s long-enjoyed ability to engage in Christian instruction or practices in public schools—and more generally to receive beneficial treatment from the government. Examples of cases that would be revisited in the 21st century (as we will see in a moment) were the 1962 Engel v. Vitale case about prayer in public schools, the 1963 Abington School District v. Schempp case about Bible readings in public schools, and the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman case that established the Lemon Test for determining whether a government act violates the Establishment Clause.[49]

Of equal or more concern to some Christians was the federal government’s application of racial nondiscrimination laws to Christian schools and universities. In the 1971 Green v. Connally case (initially Coit v. Green), the Supreme Court decided that Whites-only private schools cannot hold tax-exempt status because they were in violation of racial nondiscrimination laws. The test case concerned several “segregation academies” (or, all-White private schools) that were created in the 1960s to avoid sending White students to public schools that were desegregating, but the ruling applied to all segregated schools, including church-run schools that had long been so. This decision would apply to religious universities as well, including the segregated Bob Jones University, as determined by the Supreme Court in the 1983 Bob Jones University v. United States case. Across these court cases about religion, the Supreme Court ruled not only that public schools cannot engage in overtly religious teachings and practices, but also that the government can sometimes push private schools, including Christian schools, to relinquish their racially discriminatory policies.[50]

Image #1: Civil Rights March on Washington, DC, by Warren Leffler, 1963 (public domain)

Images #2-3: “Mississippi Freedom Summer,” flyer front and back, 1964 (public domain)

The Birth of the Modern Conservative Movement

This brings us to the fifth major transformation of this Era: the birth of the modern Conservative Movement, also called the Reagan Revolution, from around the 1970s to 1980s.[51] Just prior, the Civil Rights Movement had demonstrated how long-term planning, collective action, strategic framing, and mass mobilizing can transform public awareness and the law. Some opponents wondered what it would mean to build a counter-movement. The seeds of a new movement were being planted throughout the 1960s, as with the Barry Goldwater presidential run in 1964 that helped to define a conservative identity and policy priorities, and the tenure of Ronald Reagan as California governor in 1967-1975 that set a nationwide precedent for slashing funding for public K-12 and higher education. Arguably, seeds were being planted even for decades prior, as with the economic theories of Milton Friedman and the Chicago School of Economics in the mid-century; opposition to the New Deal and to organized labor activity earlier in the century; or opposition to Reconstruction the century prior.[52]

But it was the 1971 internal memo to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce by Lewis Powell, future Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, that galvanized such movement building by calling for organized efforts to push back on progressive social movements and the “Liberal establishment’s” attack on free enterprise, which was supposedly led by “the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians.”[53] One of the primary strategies that Powell called for was a scholarly one to cultivate the next generation of scholars to publish in journals, books, and the media; and to serve on speakers bureaus for education and the public sector. That the United States and much of the Western world were entering a period of significant post-WWII inflation (the Great Inflation, around 1965-1982) and recession (the 1970s Fiscal Crisis) at this time only fueled the desire to mobilize, particularly by placing blame on the welfare state, social reforms, and of course, schools and universities.

Soon after, what emerged was an interconnected web of four main types of organizations—foundations, think tanks, advocacy organizations, and political action committees—that worked synergistically to develop movement leaders, scholars, advocates, and media strategists.[54] Out of the Chamber emerged the Business Roundtable, which formed in 1972 as a merger of several groups, spurred not only by Powell’s memo but also by the recent successes of unions. Why unions? The period from the 1960s to early 1970s was the heyday of public sector union activity because of the occurrence of over 1000 strikes by teacher unions.[55] Not surprisingly, the Business Roundtable formed immediately after this, and by the 1980s, would place significant attention on transforming public education.

At the heart of this organizational web were not only wealthy corporate leaders but also the foundations that leveraged their massive wealth to envision, build, and sustain a unified movement. Until recently, the four most dominant were the Lynne and Harry Bradley Foundation, John M. Olin Foundation, Scaife Family Foundations, and H. Smith Richardson Foundation, together known as the Four Sisters. Other influential foundations throughout the last few decades included those funded by the Coors, DeVos, Kochs, and Walton billionaires or their families. Helping to coordinate across hundreds of philanthropies and guide their funding for the emerging large web of conservative organizations would be the Philanthropy Roundtable, which began informally in the late 1970s as a project of the Institute for Education Affairs and became a free-standing organization in 1991.

The interconnections across the emerging landscape of organizations were apparent in their shared cofounders and leaders, who included conservative Christians with tight connections to Republican leaders, then and now.[56] Two illustrative examples include Michael Joyce and Paul Weyrich. Michael Joyce held leadership roles in the Olin Foundation and Bradley Foundation, as well as the Institute for Education Studies and Philanthropy Roundtable. During the George W. Bush Administration, he led the Christian Nationalist organization, Americans for Community and Faith-Based Enterprises.

Paul Weyrich[57] cofounded several of the earliest and most influential policy-focused organizations of the Conservative Movement, including:[58]

the previously mentioned Heritage Foundation, a Christian Nationalist organization that Weyrich co-founded in 1973 with Joseph Coors (of the Coors foundations). The Heritage Foundation published its Mandates for Leadership first in 1981 and almost every four years thereafter as a conservative Christian policy guide for presidential administrations, the latest iteration being Project 2025. Much of Reagan’s policy changes reflected this guide, as is the case today with Trump.

the Republican Study Committee in 1973, which was and is to serve as the heart of conservative strategizing in Congress;

the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, also in 1973, which advances models for federal and state legislation; and

the Council for National Policy in 1981, a relatively secretive strategy group that includes leaders in the New Christian Right. Tim LaHaye was another cofounder of CNP—he also co-founded the anti-feminist Concerned Women of America in 1979. Early members have included some of the most influential of Christian Nationalist leaders, including Rousas John (R.J.) Rushdoony. More recently, members have included Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, the Federalist Society’s Leonard Leo, former Vice President Mike Pence, and former Trump advisors Steve Bannon and Kellyanne Conway. Several impactful organizations emerged out of this Council, including the Alliance Defense Fund. Members have had close ties with the Reagan, George W. Bush, and Trump administrations, and they have held leadership roles in a range of organizations shaping the current administration, including the Heritage Foundation and America First Policy Institute (many of these individuals and organizations will be described in a moment).[59]

Additionally, Weyrich had been in dialog with a number of high-profile Christian leaders in the late 1970s, helping to spur the founding of some of the other leading conservative Christian organizations of that time, including:[60]

James Dobson, who founded Focus on the Family in 1977 and the Family Research Council in 1981, and co-founded the Alliance Defense Fund in 1994. Dobson would later serve as a spiritual advisor to Trump, and his founded organizations were involved in Project 2025.

Jerry Falwell, Sr., with whom Weyrich cofounded the Moral Majority in 1979. It was Weyrich who coined the term “moral majority.”

Pat Robertson, who in 1987 founded the Christian Coalition, now called the Christian Coalition of America. He had previously founded the Christian Broadcasting Network in 1961, and he ran in the Republican primary for U.S. President in 1988.

Other key organizations and leaders (not necessarily Christian Nationalist but integral to Conservative movement building) included:[61]

the Eagle Forum, founded by Phyllis Schlafly to oppose the Equal Rights Amendment, which started initially as Stop ERA in 1972 and was renamed to Eagle Forum in 1975.

the Federalist Society, founded in 1982, which was a conservative Christian organization that would go on to significantly influence judicial appointments of Republican administrations.

Americans for Tax Reform, founded in 1985 by Grover Norquist. Norquist was a key leader in the Conservative Movement; he began leading weekly strategy meetings in 1993 that, for years, brought together a range of conservative leaders (including funders, organizational leaders and strategists, lobbyists, elected leaders, and the media) to work out differences and develop messaging strategies. Norquist was involved in the Council for National Policy; and Americans for Tax Reform remains a part of the State Policy Network.[62]

the State Policy Network, similar and connected to ALEC, which develops model state legislation, with one of its top priorities being school choice, vouchers, and charter schools. Originally started as the Madison Group in 1986, it grew into the State Policy Network in 1992. Its cofounder and president is Alabama Representative Gary Palmer, who had been displaying at his federal office the “An Appeal to Heaven” flag (a symbol of the New Apostolic Reformation, which is discussed in some detail below).

the Alliance Defense Fund, formed in 1994, now called the Alliance Defending Freedom, which is classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. ADF develops models for federal and state legislation and has led or supported dozens of impactful court cases. The current Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Mike Johnson was a former ADF attorney (and he too had been displaying at his federal office the “An Appeal to Heaven” flag).[63]

The Conservative Movement was not the same as Christian Nationalism (meaning, not all conservatives were Christian Nationalist, or even Christian), but as the above listing illustrates, the two movements overlapped significantly and helped to build one another. Christian Nationalism would feature centrally in subsequent Rightward shifts, including the ascent of the Republican Party in the mid-1990s to secure the majority of the House of Representatives for the first time in decades, the rise of the Tea Party in the late 2000s, and the Trump presidential campaigns.

—-

[40] For more on these developments and social movements, see Kumashiro (2020).

[41] For more on anti-communism and anti-LGBTQ+, see Johnson, D. K. (2023). The Lavender Scare: The Cold War persecution of gays and lesbians in the federal government. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[42] For more on anti-communism and religion, see Dallek, M. (2023). Birchers: How the John Birch Society radicalized the American right. NY: Basic Books.

[43] For more on teaching evolution, see Apple (2001).

[44] Ibid.

[45] For more on these cases, see Sands, K. M. (2025). Religion, science, and social conflict: Lessons from creationism and COVID. Isis, 116(2), 361-365.

[46] For more on higher education, see Mittal, A, & Gustin, F. (2006). Turning the Tide: Challenging the Right on Campus. Oakland, CA: Oakland Institute and Institute for Democratic Education and Culture.

[47] For more on the politicization of gender, see Butler, J. (2021, October 23). Why is the idea of “gender” provoking backlash the world over? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2021/oct/23/judith-butler-gender-ideology-backlash.

[48] For more on these developments and social movements, see Kumashiro (2020).

[49] For more on the courts and religion, see Welner, K. G. (2022). The Outsourcing of Discrimination? Another SCOTUS Earthquake. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/carson-makin.

[50] Ibid.

[51] For more on the Conservative Movement, see Apple (2001). Kumashiro, K. K. (2008). The seduction of common sense: How the Right has framed the debate on America’s schools. New York: Teachers College Press. Kumashiro, K. K. (2012). Bad teacher!: How blaming teachers distorts the bigger picture. New York: Teachers College Press. Kumashiro (2020).

[52] For more on early conservatism, see Phillips-Fein, R. (2016, May 4). The roots of American conservatism. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/the-roots-of-american-conservatism/tnamp.

[53] Powell, L. F., Jr. (1971). Powell Memorandum: Attack On American Free Enterprise System. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/powellmemo/1.

[54] For more on the web of organizations, see Kumashiro (2008).

[55] For more on teacher unions, see Kumashiro (2020).

[56] The descriptions of organizations and individuals to follow come from easily accessible online information, including websites of the organizations listed. See also, Kumashiro (2008).

[57] For more on Weyrich, see Balmer, R. (2014, May 27). The real origins of the Religious Right. Politico. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/05/religious-right-real-origins-107133.

[58] The descriptions of organizations and individuals to follow come from easily accessible online information, including websites of the organizations listed. See also, Kumashiro (2008).

[59] For more on the Council for National Policy, see GPAHE. (2025). Mapping the Authoritarian Movement: Part Three—the Council for National Policy. https://globalextremism.org/post/mapping-the-authoritarian-movement-part-three-cnp.

[60] The descriptions of organizations and individuals to follow come from easily accessible online information, including websites of the organizations listed. See also, Kumashiro (2008).

[61] Ibid.

[62] For more on Norquist, see Scherer, M. (2024, Jan-Feb). Grover Norquist: The soul of the new machine. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2004/01/grover-norquist-soul-new-machine.

[63] Fields, G., Mascaro, L., & Amiri, F. (2024, May 23). The “Appeal to Heaven” flag evolves from Revolutionary War symbol to banner of the far right. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/alito-supreme-court-flags-history-symbol-protest-a5415aeba90e21a86a50f8489fc54b7a.

Return to Table of Contents | Proceed to Part V