Return to Table of Contents | Proceed to Part III

School Times for End Times

Part II:

The Common Schools Era of the 1770s to 1860s

Establishing the Christian foundations of U.S. schooling

The Common Schools Era extended from the height of the American Revolution in the 1770s to around the end of the Civil War in 1865. This era is defined by the emergence and proliferation of the Common School, as well as the establishment of the Christian foundations of U.S. schooling.

Precursor: The Colonial Era

To set the stage, we begin by looking at what was happening just prior to the American Revolution. The seeds of what would become an Americanized Christian Nationalism were being planted during the colonial era.[9] Perhaps most known for his leading role in the Salem witch trials, the influential Congregational minister Cotton Mather in the late 17th and early 18th centuries articulated a vision for the transformation of the New World (New England and beyond) into the biblical Promised Land. In so doing, his preachings also offered religious justification for both the enslavement of Black Africans and the conquest of the Indigenous in the Americas, arguing that “The New Englanders are a people of God, settled in those which were once the Devil's territories.”[10]

The United States has never established Christianity as a state religion—and added the First Amendment specifically to resist such establishment—but even the earliest visions for the New World and the future republic were, for some people, inseparable from Christian, White, and male supremacy. That is, the identity of “American” would increasingly center on the White Protestant man, particularly through repeated patterns of state or systemic violence that further racialized and masculinized the emerging visions of American superiority, as during the militarized conflicts of the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812, as well as the internal battles related to Westward expansion (with White people attacking Indigenous people) and the repression of slave revolts (with White people attacking Black people).[11] Not all Christians shared such nationalist ideas, but such ideas would nonetheless remain the dominant strand of organized Christianity in the centuries to follow.

Pop Quiz #2: In the early colonial era, the most widely used text to teach literacy was the Bible itself, but by the late 17th century, instructional textbooks for children were being developed and used. What was the name of the most commonly used literacy textbook in the early 18th century?

(a) The Bible Reader

(b) The Children’s Primer

(c) The Literacy Series

(d) The McGuffey Reader

(e) The New England Primer

Keep reading to see the answer.

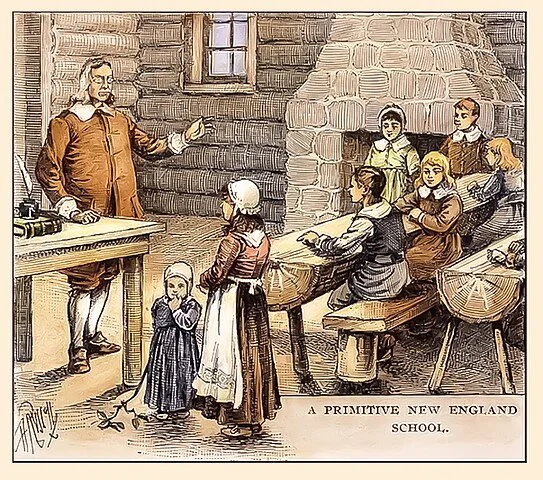

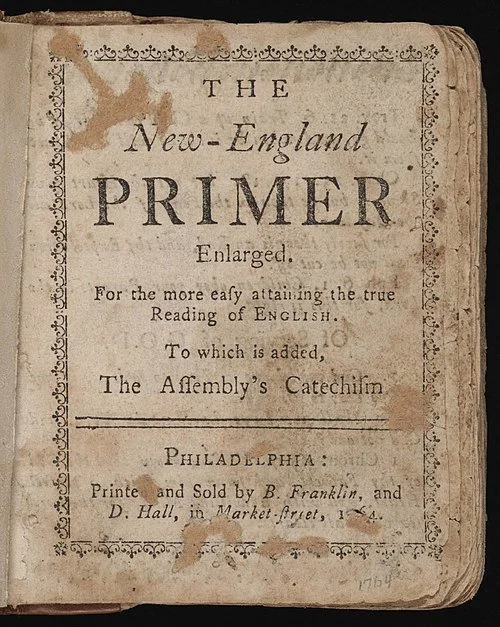

Such ideologies certainly shaped early approaches to education. Christian-based schooling was available primarily for White boys in the form of instruction for Bible literacy, occurring typically in the home through private tutoring (if the family could afford it) or in a church (if they were a member). In the New England colonies in the latter 17th century and most of the 18th century, the most popular literacy textbook was The New England Primer, in which biblical references were prominent throughout, from illustrations for teaching the alphabet and numbers to passages for practicing comprehension. Churches also engaged in missionary work with Indigenous nations and tribes, treating schooling for Native children as a primary instrument supposedly to convert and civilize. Yet, attendance was low, and not just for schools—the decades in the late 17th and early 18th centuries were a period of declining church attendance throughout the colonies.[12]

Image 1: “A Primitive New England School” (a Puritan school around 1690), artist unknown, c1850 (public domain)

Image 2: The New England Primer cover, 1764 (public domain)

Image 3: The New England Primer excerpt, 1773 (public domain)

But this was about to change. The period from around the 1730s to 1750s was the First Great Awakening, also called the Evangelical Revival, when ministers—White male evangelicals from various Protestant denominations—worked to significantly increase their church attendance, and did so successfully. As churches grew, so too did the number and size of church-run schools. Both Catholic and Protestant churches also ran “charity schools” that served poor White children in their memberships, with some churches also including children outside their memberships and outside the traditional demographics of schools, as with Quakers who included Black children in their schools. Why the focus for churches on schools? To some Protestant leaders, the Devil preferred people to be illiterate so that they could not read the Bible, making education and especially literacy antidotes to sinfulness.[13]

This was the educational context as the colonies entered their War for Independence, namely, that education was an instrument of Christianization and, for those families whose children attended their church’s school, that education was an extension of the church and the home—teaching the same lessons as did the church and protecting the children as would the home. Not surprisingly, as public schools emerged to serve the new republic and became less sectarian and more inclusive of diversity over time, and intentionally so, some would view schools as not an extension of, but an existential threat to, the home and church, and by implication, to their children, country, and God as well, making schools one of the most fundamental sites of social and political persecution and struggle since the very beginnings of U.S. history. So, too, with democracy itself, as was apparent with responses to the American Enlightenment.

The Common School and the American Enlightenment

The American Revolution spanned from around 1765 to 1783, and it was towards its end (following the Declaration of Independence in 1776) that some of the Founding Fathers and other leaders argued that building a strong foundation for a new republic required an education system that could teach, among other things, common or shared values regarding democracy.[14] Thomas Jefferson proposed among the earliest bills in Virginia in 1779 to create state-sponsored schools for precisely this purpose. In his Notes on the State of Virginia (first published in 1781), he argued that, “Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves therefore are its only safe depositories. And to render even them safe their minds must be improved to a certain degree. This indeed is not all that is necessary, though it be essentially necessary. An amendment of our constitution must here come in aid of the public education.”

Image: Recreation of East Hampton, NY Town School House c1785

(CaptJayRuffins, Town school house 02, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Starting in the 1780s, in both urban and rural areas, states launched more and more neighborhood schools, and particularly in the decades of the 1830s to 1850s, states also allocated and increased public funding for such schools. These partly public, partly private one-room schoolhouses in which students of various ages were all taught by one teacher were called Common Schools and were the predecessors of today’s public schools (although some state constitutions still use the term “common schools” today). Common Schools experienced their biggest expansion nationwide in the 1830s to 1850s, not only because of legislation and funding but also because of their championing by leaders like Horace Mann, Catherine Beecher, and Henry Barnard. Typically created by wealthy White men, the schools served their own, meaning they primarily served children who were male and White and whose families owned property. This exclusiveness persisted for nearly a century, but there were exceptions: over time more girls were “smuggled” in, and although the Common Schools never integrated, a handful of separate schools opened for Black children who were not enslaved.[15]

One of the most significant philosophical influences over the Common Schools was the American Enlightenment, which almost exactly overlapped with the Common Schools Era. Stretching from the mid-18th century (just before the American Revolution) to the mid-19th century (just before the Civil War), the American Enlightenment was filled with intellectual and philosophical activity—especially about equality, liberty, religious tolerance, and science—that laid the groundwork for the American Revolution and subsequently shaped the development of early U.S. governance and civic life. As a result, for some political and educational leaders, Common Schools were meant to be nonsectarian or nondenominational.[16] I will describe in a moment how such was never the case and Common Schools were actually quite explicitly Protestant—particularly, Calvinist—but it is important to appreciate why religious tolerance and nonsectarianism were so important and contested.

The First Amendment to the Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” These two phrases, known as the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause—which together constitute freedom of religion—protect our freedom from being coerced into practicing any particular religion (as when the government or the majority attempts to establish an official or state religion or to pass laws that aid a religion or prefer one religion over another) and protect our right to exercise or practice one’s own religion (whatever religion or faith that may be). These concerns were due less to Christians fearing coercion by non-Christians, and more to Christians fearing coercion by other Christians, reflecting long-standing tensions between Catholics and Protestants as well as between one Protestant denomination and another. As in Europe and as in the American colonial era, there had never been just one way to be Christian and there had always existed tension between groups over whose Christianity would prevail, in schools or otherwise.

From their beginnings, Common Schools and the forthcoming public schools were sites of religious struggle, with some people concerned that schools were not Christian enough or in the right way, as illustrated by conflicts over which version of the Bible to read and which prayers to recite.[17] The criticisms about Common Schools leader Horace Mann were illustrative: although he was attacked as irreligious, the primary concern was not that he was not Christian (he was Unitarian), but that he was not pushing for Christianity to be practiced in schools as some would have preferred. So too, by the way, a century later with the influential education leader and philosopher John Dewey, who was Christian but criticized for not promoting Christianity in schools in the right way—and instead, for promoting a curriculum based on experimentation, which was considered to run afoul of the absolutism of the Bible.

A similar inter-religious tension was visible in Christian Nationalist calls for the United States to be a Christian state that was happening at around the same time. In 1864, the National Reform Association (an organization of Reformed Presbyterians), part of the Christian Amendment Movement, called for a constitutional amendment to name Christianity as the official state religion. It read in part, “‘We the people’ would acknowledge ‘Almighty God as the source of all authority and power in civil government, the Lord Jesus Christ as the Ruler among nations, His revealed will as the supreme law of the land, in order to constitute a Christian government.’” But not all Christians—not even all Christian Nationalists—agreed with having such an amendment, given the widening divide between churches and denominations over whose Christianity would be centered.

In addition to the development of philosophical and legal frameworks about democracy, the American Enlightenment was filled with research and scholarly activity in science and technology, helping to bring about the First Industrial Revolution. Occurring in the late 18th to mid-19th centuries, the First Industrial Revolution was a time in which technological innovations contributed to industrialization, namely, with the use of machines and mechanized manufacturing that would profoundly transform commerce, labor, and the economy—and schooling as well.

The Christian Foundations of Teaching and Teachers

These two ideological shifts of elevating nonsectarianism and elevating science and technology were seen by some as a threat to Christianity’s singular influence over everything from governance to culture to schooling. Thus we see the Second Great Awakening occur from around the 1790s to 1840s, which was a second period of revivals among Protestants that involved not only the growth of existing churches but also the emergence of reform movements, new denominations, and a missionary zeal. This revivalism was so impactful that Protestantism would continue to dominate various aspects of society for the entirety of the 19th century, including schools. Although intended by some to be nonsectarian, Common Schools were far from such. Protestantism, particularly Calvinism (such as Reformed, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and related denominations) was dominant among the influential education leaders in the Northern states at this time, and it therefore permeated the Common Schools that spread throughout the country. Protestantism shaped a number of aspects of schools, including what was being taught and who was doing the teaching.[18]

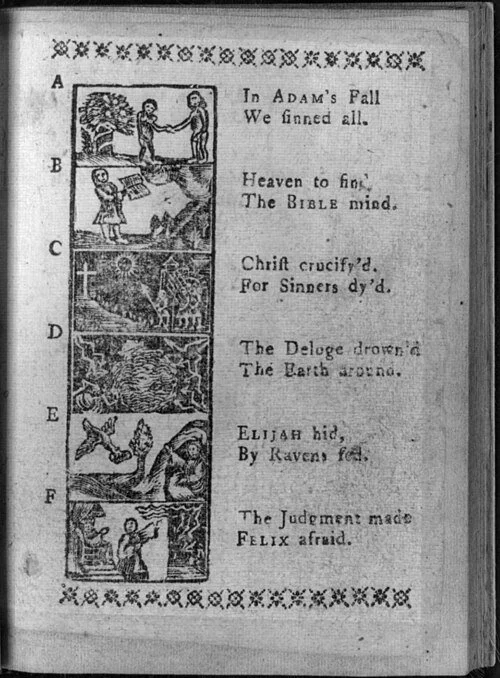

Regarding what was being taught, let’s look at the curriculum in both the Common Schools and the American Indian boarding schools. In the Common Schools from the 1830s onward, the most widely used textbook was the Eclectic Readers, also known as the McGuffey Readers, which in their initial versions were filled with biblical lessons, including Calvinist narratives as a way to teach morality (such as through fire-and-brimstone stories of how immoral people were to be condemned to Hell). The original Readers are still in use by some private schools and homeschoolers today.

Image: The Eclectic First Reader, 1841 (public domain)

Pop Quiz #3: Please complete the McGuffey’s Second Reader (level 2), Lesson XXXV, “Praise to God”:

Come, let us praise God, for he is exceedingly great; let us bless God, for he is very good.

He made all things; the sun to rule the day, the moon to shine by night.

He made the great whale, and the elephant; and the little worm that crawleth upon the ground.

The little birds sing praises to God, when they warble sweetly in the green shade.

The brooks and rivers praise God, when they murmur melodiously among the smooth pebbles.

I will praise God with my voice; for I may praise him, though I am but a little child.

A few years ago, and I was but a little infant, and my tongue was dumb within my mouth.

And I did not know the great name of God, for my reason was not come unto me.

But I can now speak, and my tongue shall praise him; I can think of all his kindness, and my heart shall love him.

Let him call me, and I will come unto him; let him command, and I will obey him.

When I am older, I will praise him better; and I will never forget God, so long as my life remaineth in me.

What is the subject of this lesson? Who made the sun, and moon, and all things that live upon the earth? Who is it that has protected you from harm, and now keeps you alive? Will God listen to the praises of little children? Should you not, then, praise God for his goodness to you?

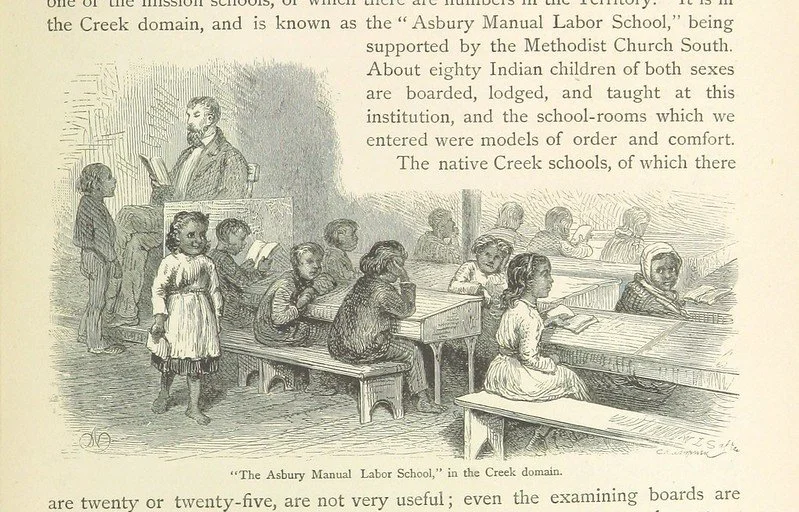

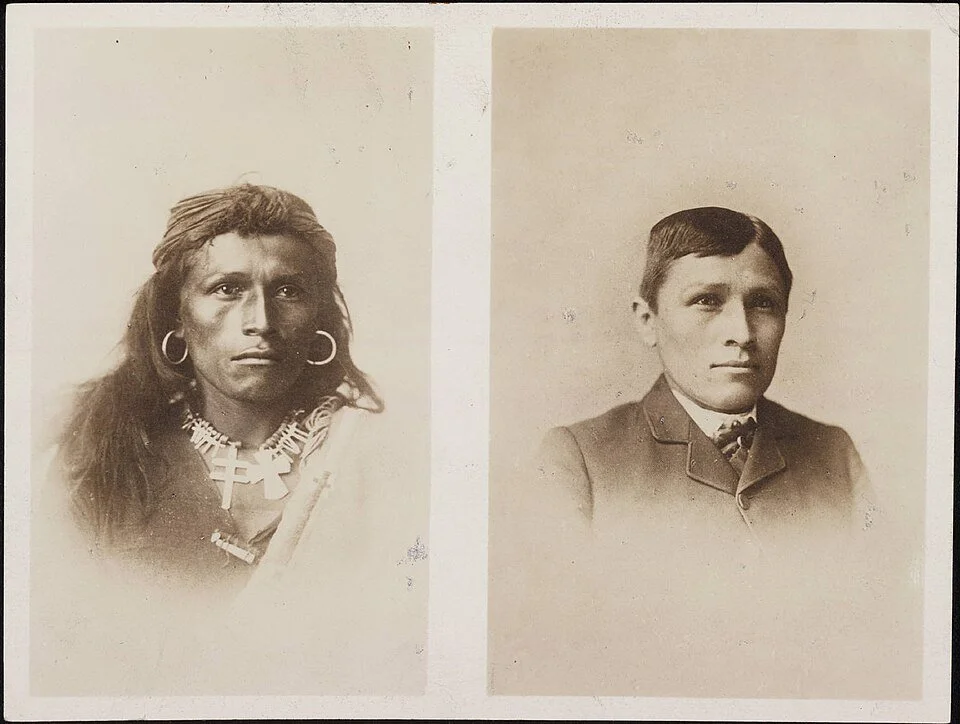

Similarly, federally run American Indian or Native American boarding schools (also called residential schools) aimed to Americanize by supposedly erasing Indigenous identity and culture through Christianization. Unlike the Common Schools and the forthcoming public schools that were in the domain of state governments, these boarding schools were run by the federal government and the military, in partnership with various churches. Christian schools for Native American children first emerged in the 17th century, but they rapidly expanded in number and enrollment across the continent throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1792, the U.S. government began paying missionaries for this work, and subsequently, it was the Indian Civilization Act of 1819 that would fuel the growth of schools nationwide. U.S. General Richard Pratt, the founder of the flagship of such schools, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, captured this goal of Americanization with his infamous phrase, “kill the Indian, save the man,” a process of erasing indigeneity for which conversion to Christianity was a central component. Pratt used images like the before-and-after photograph of the Navajo young man Tom Torlino (in 1882 upon entering Carlisle in traditional attire, and then in 1885 with reformed appearance) as proof that such conversion was possible. Between their own missionary endeavors and their formal partnerships with the federal government, nearly every denomination—Catholic and Protestant—engaged in attempting to educate (and convert and civilize) Indigenous children during this time period.[19]

Image #1: “The Asbury Manual Labor School,” a school for Creek students 1822-1830 (from E. King, “The Great South”; public domain)

Image #2: “Tom Torlino, Navajo, before and after,” 1882-1885 (public domain)

The missionary reach of churches extended well beyond national borders but were nonetheless integral to nation building. The first missionaries to Hawai‘i (almost a century before Hawai‘i became a U.S. territory) were Calvinists from Boston who arrived in 1820 and were part of a larger influx of business leaders looking to expand markets and political leaders looking to expand the U.S. empire. Among the earliest schooling endeavors was an informal school, referred to as Mrs. Bingham’s School, started in 1820 by Sybil Moseley Bingham, wife of missionary Hiram Bingham, soon after the first arrivals to the islands. The oldest high school west of the Mississippi River, Lahainaluna High School on Maui, was founded in 1831 as Lahainaluna Seminary. Subsequently, it was missionaries (White Protestant men from the United States) who were appointed sequentially into the newly created position of Minister of Public Instruction as part of the first Cabinet of the independent Hawaiian kingdom in the mid-1840s and who would exert much influence over the emerging public school system. These leaders echoed the goal of American Indian boarding schools as they aimed to educate, convert, and civilize Native Hawaiians—that is, supposedly to save Native Hawaiians from themselves through Common Schools and Christian teachings. But to be clear, the educational system in Hawai‘i was not entirely imposed from outsiders: the public school system and position of Minister of Public Instruction were created by King Kamehameha III, and the original superintendent and deputies of public instruction as well as the vast majority of teachers in public schools throughout the 19th century were Native Hawaiian. The White missionaries worked in consort with Native Hawaiian leaders to create and lead the public schools, sometimes in agreement and sometimes in conflict, including over Christian instruction.[20]

Protestant missionaries also created the early elite private schools in Hawai‘i, namely, the Chief’s Children’s School (founded in 1840 as a boarding school for the children of Hawai‘i’s highest chiefs, later renamed Royal School, and subsequently converted to a public elementary school), Punahou (founded in 1841), and ‘Iolani (founded in 1863 initially as St. Alban’s College). All three would go on to offer a Christian education to Hawai‘i’s royalty and other Native Hawaiians. White Christians would even influence the curriculum of the private school later created by and for Native Hawaiians, namely, the Kamehameha Schools, founded in 1887 through the trust of the late Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. One theme throughout all schools serving Native Hawaiians was a fixation on Christianizing their supposedly deviant genders and sexualities.[21]

Punahou is particularly illustrative of the links between missions and imperialism: initially created for children of White missionaries, its graduates and their missionary kin would go on to play key roles in the gradual weakening of the monarchy, its overthrow in 1893, and annexation in 1898, and they would subsequently assume key positions in the imposed new government. Punahou’s own narrative about its founding points to its missionary and colonial origins, explaining that those first missions were inspired by contact a few years prior in New England with a young Native Hawaiian orphan, Henry ʻŌpūkahaʻia, who would convert to Christianity but die soon after. In 1818, during his funeral, the influential Congregational minister Lyman Beecher interpreted the youth’s death as God’s way of “saying to us, more audibly than ever, ‘Go forward,’” and indeed, missions to Hawai‘i began soon after.[22]

Image #1: Henry ʻŌpūkahaʻia, artist unknown, 1820 (public domain)

Image #2: Mrs. Bingham’s School, by George Holmes, c1821 (public domain)

Image #3: Adobe Schoolhouse and Kawaiahao Church (original building of the oldest church on Oʻahu), by Clarissa Armstrong, c1832 (public domain)

Image #4: King Kamehameha III and Queen Kalama, by Paul Plum, 1846 (public domain)

Christian evangelicalism and Western colonialism have long supported one another, perhaps best illustrated by the series of papal bulls in the 15th century, known now as the Doctrine of Discovery, that called on Catholic nations to colonize the New World and spread Catholicism to its Indigenous peoples. In the first such statement by Pope Nicholas V in 1452, Christians were to “invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens [Arabs and Muslims] and pagans whatsoever, and other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and to reduce those persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods, and to convert them to his and their use and profits.” This Doctrine accelerated the Age of Discovery (or, Age of Exploration), which is the era from the 15th to 17th centuries when European nations extended their empires westward and southward using missionary cover to justify extraction of resources, enslavement of indigenous peoples, and extermination of anyone who got in the way.

Centuries later, this Doctrine would come to inform U.S. law and policy, particularly regarding Indigenous rights, as in the 1823 Supreme Court case of Johnson v. M’Intosh, which invoked the Doctrine in its ruling that Native Americans had rights to occupy land but not to own it, and therefore that White explorers could usurp Native lands as their own. This ruling would help to propel Westward expansion, as did the Monroe Doctrine, also dating to 1823, which purported that the Americas were no longer open to European colonization and were to be under U.S. control. Westward expansion throughout the 19th and 20th centuries was further propelled by Manifest Destiny, the notion that America was ordained by God to control North America (an early form of postmillennialism, as will be discussed shortly). Manifest Destiny was a centuries-old notion that gained prominence in the 1840s as justification for not only colonization but also expansion of slavery into new territories, using religion as a cover. Influential news columnist and editor John O’Sullivan helped popularize the term, as in 1845 when calling for “the fulfilment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”[23]

Protestantism was also influencing who was doing the teaching in American schools. From the beginning to the middle of the 19th century, the teaching profession changed from almost entirely men to women constituting the vast majority. One factor for this transformation was economic: as schools grew and the demand for teachers grew, the prestige and salaries of teachers declined, prompting men to seek other professions. But another key factor was socio-cultural: White, young, unmarried but heterosexual, Christian women, in particular, were recruited for this role, with expectations that they could be effective not just for academic instruction but also for moral instruction, and not just for White students but also for students of Color and Indigenous students, all of whom were to be socialized through Christian teachings. Gender and sexual purity (or, more accurately, sexual normativity) was of paramount importance, given how racist stereotypes of non-Whites often portrayed them as having abnormal genders and immoral sexual behaviors (as previously mentioned regarding Native Hawaiians). Yet, women teachers occupied these roles in contradictory and complex ways, and moral panics about how they might be tainting youth occurred throughout the era and beyond, particularly regarding any signs that the teachers were of a “third sex,” that is, exhibiting and thus potentially transmitting a deviant gender or sexuality (which is a moral panic about queerness, transness, and grooming that will repeat in subsequent centuries).[24]

In the 1820s to 1850s, Catherine Beecher, daughter of the minister Lyman Beecher (just mentioned), was a champion for women’s and girls’ education and was among those who played a significant role in shifting the tide to recruiting more young women into teaching, including for Westward expansion, and would do so by emphasizing the Christian imperative of this profession. In one of her final writings, she explains, “Woman's great mission is to train immature, weak and ignorant creatures to obey the laws of God; the physical, the intellectual, the social and the moral.”[25] By the middle of the 19th century, the White Christian woman came to symbolize the assimilating function of American schools—in Common Schools, boarding schools, or otherwise. Such symbolism was embodied by the 1872 painting by John Gast, American Progress, in which Columbia (the White female personification of the United States), with “The Star of the Empire” on her forehead, floats Westward, bringing technology in one hand and education in the other, with settlers following her and urbanization not far behind, as Indigenous people and wildlife flee.[26] White Christian women would persist as the face of the teaching profession as the modern public school system emerged.

Image: “American Progress,” by John Gast, 1872 (public domain)

—-

[9] For more on Christianity in the colonial era, see Gorski & Perry (2022).

[10] Mather, C. (1693). Wonders of the invisible world.

[11] Gorski & Perry (2022).

[12] For more on colonial era schooling, see Apple (2001). Kaestle, C. F. (1983). Pillars of the republic: Common schools and American society, 1780-1860. New York: Hill & Wang.

[13] Ibid.

[14] For more on the Common Schools, see Apple (2001). Kaestle, C. F. (1983). Pillars of the republic: Common schools and American society, 1780-1860. New York: Hill & Wang.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] For more on schooling for Native Americans, see Pember, M. A. (2025). Medicine River: A story of survival and the legacy of Indian Boarding Schools. NY: Pantheon. Spring, J. (2009). Deculturalization and the struggle for equality: A brief history of the education of dominated cultures in the United States. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[20] For more on education in the Hawaiian kingdom, see Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, N. (2014). Domesticating Hawaiians: Kamehameha Schools and the "tender violence" of marriage. In B. J. Child (Ed.), Indian subjects: Hemispheric perspectives on the history of indigenous education (pp. 16-47). Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press. Kaomea, J. (2014). Education for elimination in nineteenth-century Hawai`i: Settler colonialism and the Native Hawaiian Chiefs’ Children’s Boarding School. History of Education Quarterly, 54(2), 123-144. Niiya, M. (2024). A Punahou mo‘olelo: The creation of institutional memory and myth. Settler Colonial Studies. DOI: 10.1080/2201473X.2024.2408154.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Niiya (2024).

[23] O’Sullivan, J. (1845). The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, 17.

[24] For historical analyses of teachers, women, and gender, see Blount, J. M. (2005). Fit to teach: Same-sex desire, gender, and school work in the twentieth century. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Meiners, E. R. (2007). Right to be hostile: Schools, prisons, and the making of public enemies. New York: Routledge.

[25] Beecher, C. E. (1872). Woman's profession as mother and educator: With views in opposition to woman suffrage.

[26] Meiners (2007).

Return to Table of Contents | Proceed to Part III