Return to Table of Contents | Proceed to Part IV

School Times for End Times

Part III:

The Early Public Schools Era of the 1860s to 1940s

Developing the two-prong strategy for Christian Nationalist activism in schools

The Early Public Schools Era spanned from the end of the Civil War in 1865 to around the end of World War II in 1945. This era is defined by the transition to the modern public school system, as well as the development of the two-prong strategy for Christian engagement in public schools.

Northern Urbanization and Southern Reconstruction

Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, U.S. schooling began to transition from the independent small Common School into much larger public schools clustered in districts that were, at least theoretically and partially, funded and governed by the public sector. This emergence of public school systems resulted primarily from four profound transformations that the country was experiencing, mostly in Northern and Midwestern regions.[27]

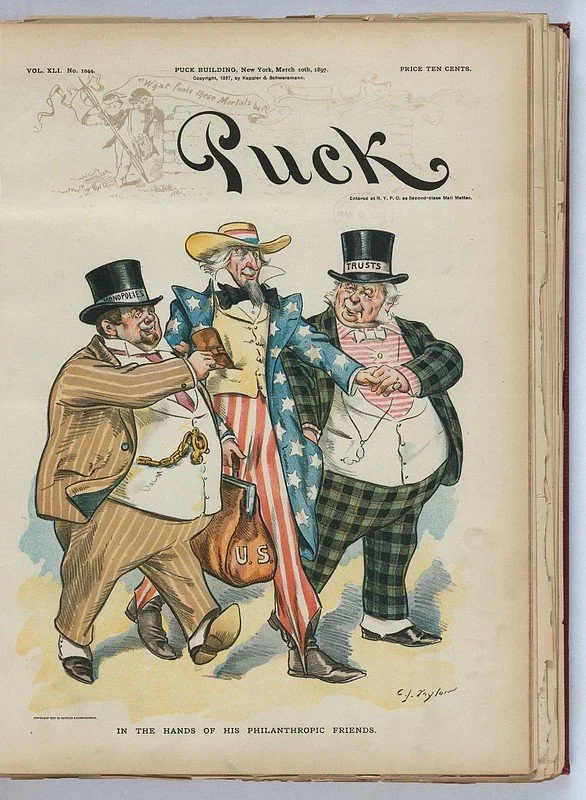

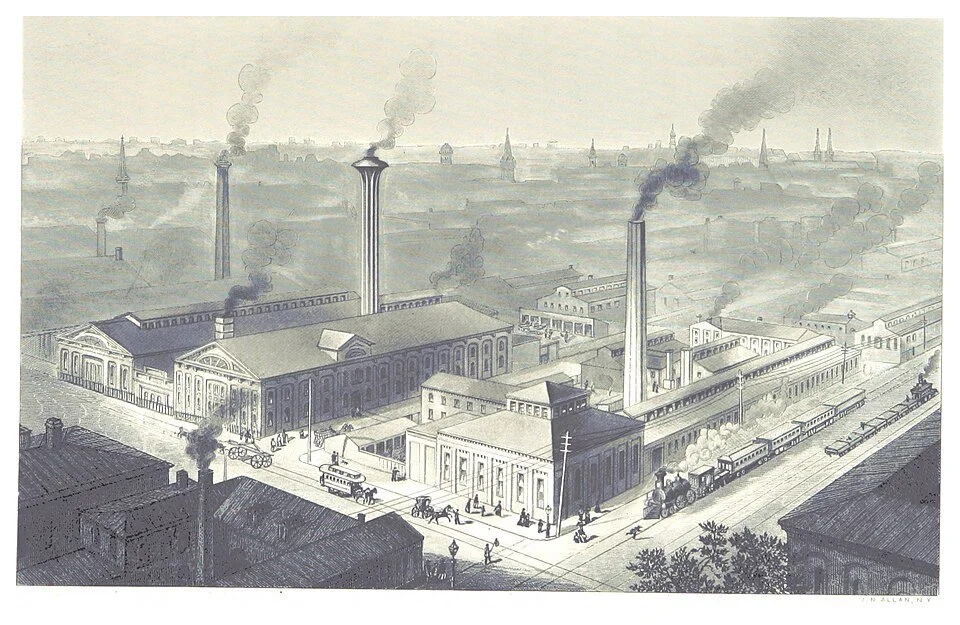

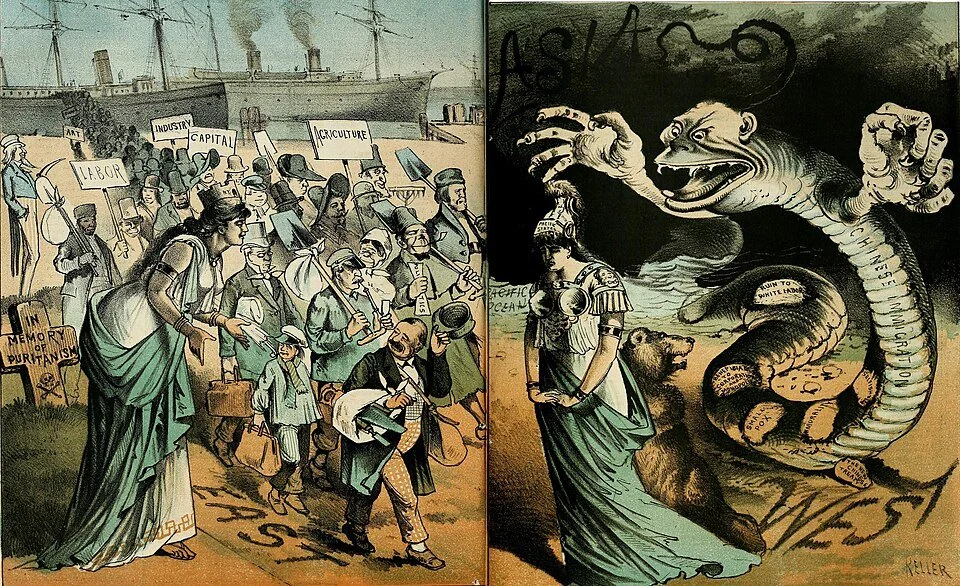

First was industrialization, particularly the Second Industrial Revolution from around the 1870s to 1910s that consisted of significant expansion of manufacturing and production, most visibly by way of factories, leading to economic growth and the widening wealth gaps reflected by the Gilded Age of this era. With the growth of larger and larger hubs of industry came the second major transformation in the same time period, namely, urbanization and the emergence of cities with more diverse, concentrated, and increasingly large populations. As both factories and cities grew, so too did the number of jobs to support them, leading to the third transformation: immigration. From the 1880s to 1920, well over 20 million immigrants arrived to the United States, and they mostly settled in these emerging cities. The immigrants of this era were notable for their religious diversity—bringing many more Catholics and Jews than before—but also for their racial homogeneity: they hailed primarily from Europe and were mostly White people. This racialized immigration was no accident: at a time when the country was facilitating immigration from Europe, it was also building more and more race-based barriers to immigration from other regions, particularly from Asia, illustrated by such legislation as the Naturalization Act of 1870, Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907, Immigration Act of 1917, and Asian Exclusion Act of 1924. The 1881 cartoon, “Immigration East and West” (published in The Wasp), illustrates this racist distinction with two panels: on the left, “Westward, the course of empire takes its way,” European immigrants bring virtues, while on the right, “Eastward, the march of national decay,” Chinese immigrants bring threats.

Image #1: “In the Hands of His Philanthropic Friends” (cartoon about the influence of the wealthy over government), in Puck, 3/10/1897 (public domain)

Image #2: Philadelphia (depicting industrialization), 1876 (public domain)

Image #3: “Immigration East and West,” in The Wasp, 8/26/1881 (public domain)

Yet, White people were not the only ones flowing to the cities in large numbers. Towards the end of this era, in addition to immigration from abroad, large migrations to the emerging cities included Black people from the Southern United States. In the Great Migration of around the 1910s to 1970s, millions of Black people left the Jim Crow Southern states and settled in Northern, Midwestern, and Western states. Now faced with populations of students that were of size and diversity like never before, the schools, too, needed to evolve: with enrollments of not dozens but many times that number of students, schools created multiple classrooms that separated students by age and, for older students, by subject areas as well. Tracking systems separated students by race and class, while purportedly separating them by academic ability. Multiple schools emerging in the same geographic region were grouped administratively into one school district. More and larger schools required more teachers, and to train them, “normal schools” (or, teacher-preparation academies) spread throughout this era as well, with women almost entirely dominating enrollments, a trend that continued as these schools morphed into or were replaced by colleges of education throughout the 20th century. Much of the public-school system that we are familiar with today—with its differentiated classrooms and curriculums, centralized administrations, professionalized and gendered teaching force, racially segregated students, inequitable funding, and so on—trace back to these transformations.[28]

At least, for some regions it does. As mentioned previously, the four transformations of industrialization, urbanization, immigration, and the Great Migration were more profound in the Northern and Midwestern regions. Although the Southern states also transitioned from Common Schools to public school systems, their path was more contested. In the formerly slave-holding states of the South, what fueled discontent with the federal government was not only the recent defeat in the Civil War, but also the federal consequence of that loss, which was Reconstruction, the period often dated from 1863 (emancipation) to 1877 (the withdrawal of federal troops from the South). Reconstruction centered on the abolition of slavery and the reintegration of the former Confederate states, and some of its achievements toward protecting and supporting the newly freed were legislation (like the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments) and initiatives (like the Freedmen’s Bureau). Two education-related events during Reconstruction are noteworthy.[29]

Pop Quiz #4: In what year did the United States first create a federal Department of Education?

(a) 1787

(b) 1827

(c) 1867

(d) 1947

(e) 1977

Bonus: When did the United States pass legislation to recreate a federal Department of Education?

(a) 1789

(b) 1829

(c) 1869

(d) 1949

(e) 1979

Keep reading to see the answers.

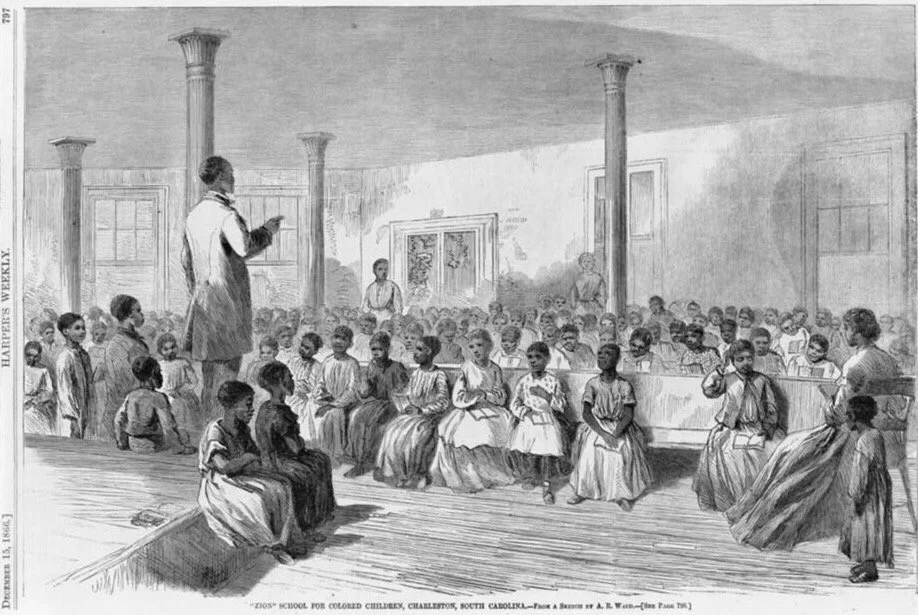

From 1865 to 1872, the federal government established a new agency, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and other initiatives to provide immediate and temporary assistance to Black refugees and newly freed people and families as they transitioned to a new life in the South. Education figured centrally in this work. For Black people, prior to the Civil War, literacy instruction was illegal in many places in the South, and not surprisingly, with the abolition of slavery and with Reconstruction, many Black communities across the South worked eagerly to build their own schools for the first time. Schools built with the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau were often called Freedmen’s Schools. Building schools for White people was also a priority for the federal government, given that, prior to the Civil War and compared to the North, Southern schools were less widespread and, in the eyes of some, of much lower quality. Some Northern leaders credited the Common Schools in the North for providing the moral foundation for abolitionism, and thus, were keen to see the school systems of the South rapidly developed for White students. Whether for Black students or for White, one of the main collaborators for creating new schools in the South were Northern churches, given the centrality of Christian instruction in public schools.[30]

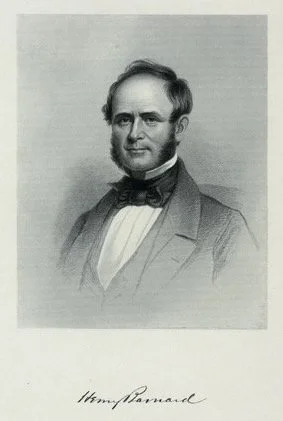

In 1867, the federal government established, for the first time, the U.S. Department of Education, initially tasked with gathering comparative data to ensure that students across the country were receiving a quality education, including Black students in the South. The influential champion of Common Schools mentioned previously, Henry Barnard, would be appointed the first U.S. Commissioner of Education to lead this tiny new Department. Under attack since its inception, in part because of its race-conscious role, the Department lasted barely a year before being downsized to an Office of Education and moved to within the Department of Interior (and a federal Education Department would not be reconstituted until more than a century later).[31]

Image #1: Freedmen’s School, James Plantation, North Carolina, 1866 (public domain)

Image #2: "Zion School for Colored Children, Charleston, South Carolina” (a school organized and run by Black people), in Harper's Weekly, 12/15/1866 (public domain)

Image #3: Henry Barnard, by Thomas Addis Emmet, 1880 (public domain)

Both of these developments—new schools and federal initiatives—were opposed by some Southern politicians and newly emerging White Christian Nationalist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (founded in 1865). This opposition was fueled rhetorically by such cultural narratives as the “Lost Cause” (or, Lost Cause of the Confederacy), which purported that the Confederacy had fought a just and Christian war and would be redeemed in the future. Such groups burned down hundreds of schools for Black students during Reconstruction—in some instances, the same school more than once after being rebuilt. The attacks happened not only because the attackers opposed education for certain groups, but also because they viewed these developments and pretty much any federal actions at that time as akin to Reconstruction, which ultimately was their bane. Reconstruction and racial justice played a key role in catalyzing this newest, reactionary phase of Christian Nationalism in public education, which was more explicitly intertwined with White Nationalism and with political activism than before (a pattern that will be repeated and intensified a century later in reaction to the Civil Rights Movement).[32]

Opposition to Reconstruction finally brought about its end with the contested presidential election and Compromise of 1877 that, at its core, involved withdrawing federal troops from the South. This defeat of Reconstructionism paved the way not only for Jim Crow or legally mandated segregation in the South, but also for Imperial expansion Westward and intensified genocide—it was the federal troops withdrawn from the South, after all, that would now be deployed against Native Americans, accompanied by schools that aimed to Americanize through Christian teachings. Thus we see how various forms of racialized violence were bolstering and being bolstered by Christian Nationalism: the spread of U.S. wars, acceleration of Westward expansion, and proliferation of anti-Black lynching were all rationalized as religiously righteous, and in the case of lynching, were sometimes performed as a religious ritual.[33] As before, there was diversity of thought among Christians—with some arguing that opposition to such violence was religiously righteous—reflecting how Christian Nationalist rationalism may have been a dominant narrative, but was a contested one as well.

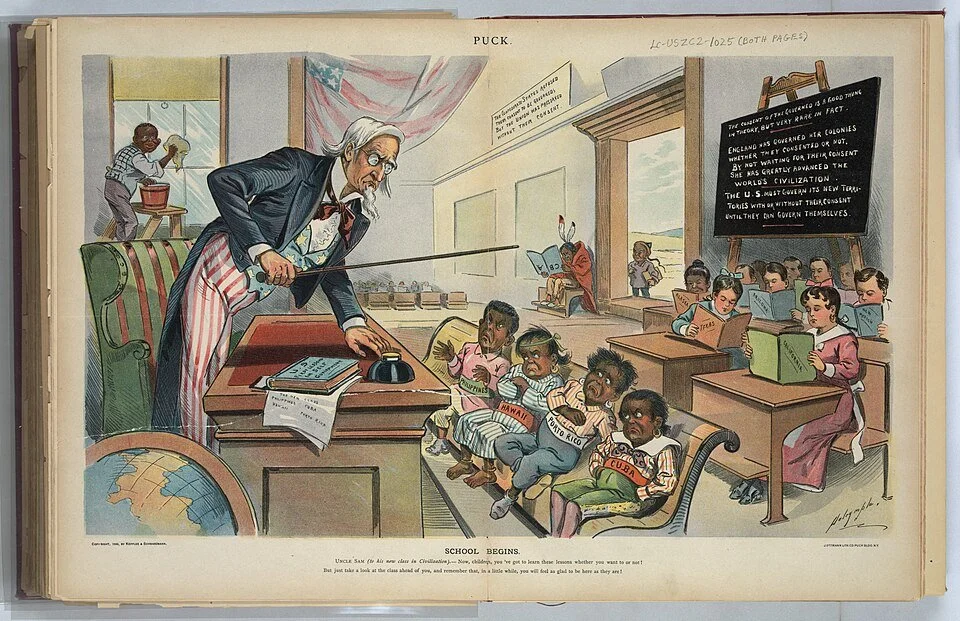

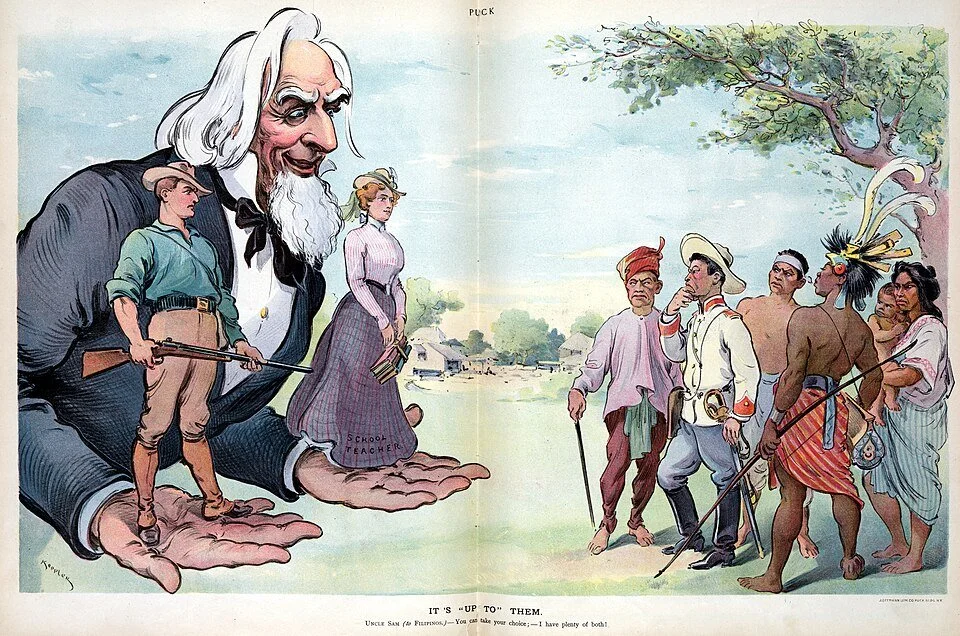

Accompanying the militarized violence was cultural violence. Let’s turn again to Hawai‘i, this time following the overthrow of the last Hawaiian monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, and the onset of illegal occupation and eventual annexation in the late 19th century. Building on the early missionary efforts to supposedly save Native Hawaiians from themselves, what followed the overthrow were even more widespread efforts in Hawai‘i to “denationalize” through the education system by erasing Native Hawaiian culture, language, and identity in order to promote assimilation. So too with a number of occupied lands, as illustrated in the 1899 cartoon, “School Begins” (published in Puck), with students labeled Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Cuba sitting in the front; the caption reads, “Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization) Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!” Or more bluntly, in the 1901 cartoon, “It’s ‘Up To’ Them” (also published in Puck), in which Uncle Sam faces a group of men from different cultures, holding up a male soldier in one hand and a female “School Teacher” in the other, with the caption reading, “Uncle Sam (to Filipinos.)—You can take your choice;—I have plenty of both!” Also in Hawai‘i at that time were attempts to erase “foreign” or “alien” culture, language, and identity, for example, by way of the Americanization curriculum for Japanese immigrants in Hawai‘i in the early 20th century. As with the Americanizing teachings in North American, a central tool for accomplishing such cultural genocide in Hawai‘i was Christianization, as reflected in the public statements by a series of White superintendents of public instruction and other leaders in Hawai‘i throughout the first half of the 20th century that repeatedly paid homage to the early missionaries for raising the moral and civic consciousness of the Native people. This was done not only through the curriculum, but also through the selection, training, and supervision of the teaching profession.[34]

Image #1: Queen Lili‘uokalani, c1898 (public domain)

Image #2: “School Begins,” in Puck, 1/25/1899 (public domain)

Image #3: “It’s ‘Up To’ Them,” in Puck, 11/20/1901 (public domain)

Christianization was so pervasive in Hawai‘i that it was significantly shaping Hawaiian culture itself, including the arts. Whereas Hawaiian song and dance were sometimes forms of resistance to Western and religious imperialism, they were at other times incorporating and conveying those very ideologies. Some of the most popular songs in Hawai‘i that date back a century or more have deeply Christian themes. Hawai‘i Aloha, also called Ku‘u One Hanau, a song that celebrates God’s blessing and protection, was written by influential Congregational minister Lorenzo Lyons around the mid-19th century—this song was in the running to be the state anthem when Hawai‘i became a state, and although not chosen as the anthem, it is still today sung at various official public events, including the opening sessions of the state House and Senate and the inauguration of the governor. He Mele Lāhui Hawaiʻi (Song of the Hawaiian Nation), composed in 1866 by the future queen Lili‘uokalani, takes the form of a prayer to God by the nation, and was the national anthem for Hawai‘i for ten years (replaced in 1876 by Hawai‘i Pono‘ī, which remains the state anthem). And a popular song that we frequently sang in school when I was growing up, Iesu Me Ke Kanaka Wai Wai (Jesus and the Rich Man), is about a parable from the New Testament, written by the prolific musician John Kameaaloha Almeida, known as the Dean of Hawaiian Music, originally in 1917 but recorded in the current form in 1947. None of this should be surprising, given that Christian teachings were intended to occur in a number of ways—not only through the church and through schools, but through the arts as well. The first publication of Hawaiian songs was a hymnal published by missionaries in 1823, and in subsequent decades, more would be published, from which we get some songs still performed today, including on soundtracks to television shows and films that supposedly occur in Hawai‘i.

Deinstitutionalization and Re-Christianization

One of the most important developments within organized Christianity in this era was a divergence in how people were responding to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Two opposing strands of Christian theology became increasingly prominent (and both would reemerge in prominence a century later following the Civil Rights Movement): postmillennialism and premillennialism.

As the United States approached the Civil War, some Christians had argued that their religion called on them to oppose and even work to end slavery. This pull towards socio-religious engagement and service helped to usher in the Third Great Awakening, spanning from around the late 1850s (pre-Civil War) to the 1930s (pre-World War II). This era was characterized by the popularity of postmillennialism, which at its core, was the notion that the Second Coming of Christ can happen only after Christian ethics have come to prosper around the world for a millennium; that is, Christians must first make the world more Christian. Some Protestants interpreted this to mean that they should become far more involved in political activism or social reforms at home and in missionary work abroad, and such activity intensified with the related Social Gospel Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which aimed to apply Christian ethics to a wide range of social and economic problems, most notably at the time, slavery, poverty, and alcoholism. As the 20th century progressed and with the decline of the Social Gospel Movement, postmillennialism became less associated with social service and more focused on elevating Christianity in various societal sectors (as we will see with the rise of dominionism).[35]

At the same time, a counter movement gained prominence, at first much smaller in numbers but no less influential by the latter half of the 20th century. This was called the Great Reversal: in contrast to postmillennialism and the Social Gospel, the counter movement focused on premillennialism, the notion that the Second Coming of Christ can happen only just as the world is about to face the End Times, or the apocalyptic moment when the world is to end as we know it (as with Armageddon), which can happen in any number of interconnected ways, including socially, politically, economically, environmentally, morally, and so on. The path forward, in this view, was not to integrate with and serve a diversifying society, but rather to separate from and fight to protect oneself within an increasingly hostile world (that is, to prepare for and engage in a war between good and evil), even if that means fighting against other Christians, including the larger, more liberal Protestant majority of the time—or, for that matter, even if that means fighting against secular laws, civil society, and democratic institutions. Unlike the Social Gospel’s focus on reforming society through service and liberalism, the focus here is on saving souls through evangelism and spiritual purity. In the 1910s, this strand is what birthed the modern Christian Fundamentalist Movement.[36]

Clearly, there were multiple approaches to Christian engagement with public schools. While some postmillennialists were most active in Reconstruction-related and missionary-related efforts to spread Christian teachings, both postmillennialists and premillennialists were leading the legal battles over public school curriculum and policy; and although various denominations continued to offer church-run schools, Catholics were by far the most active in doing so during this era, partly in response to the Protestant-centric nature of public schools. Together, these groups planted the seeds for what would become the complementary two-prong strategy for engaging with public schools that still persists today: deinstitutionalization (or, separating from) and re-Christianization (or, taking control of).[37]

Deinstitutionalization aimed to lessen the educational and political significance of public schools by turning to or creating alternative institutions to educate Christian children. The massive growth of Catholic schools during this era was an example.

On the other hand, re-Christianization aimed to return, maintain, or otherwise increase the presence of state-sponsored or state-protected religious expression and instruction in public schools. One example was the push for the 1875 Blaine Amendment, which would have banned public funding for religious schools, and though it failed at the federal level, similar amendments would go on to pass in a number of states. How does banning public funding for religious schools support re-Christianization? Although seemingly an attempt to maintain the separation of church and state, the underlying motive was by Protestants to slow the movement to expand Catholic education by keeping public funds away from Catholic schools. Given how public schools were permeated with Protestant doctrine, like in the curriculum, the attempt to keep public funds in public schools was ultimately aiming for re-Christianization—that is, aiming to maintain the status quo in which Protestantism dominates, not unlike how today’s calls for “colorblindness” are really calls to maintain the status quo in which Whiteness dominates. Not surprisingly, the Blaine Amendment was recognized even then as anti-Catholic and, because the growing Catholic population resulted from increased European immigration, as anti-immigrant as well.

Pop Quiz #5: Which two statements are true?

(a) Widespread organized efforts to ban the teaching of evolution did not begin until the 1920s.

(b) Thirteen states had passed laws restricting the teaching of evolution in schools by 1925.

(c) The Scopes Trial was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1925.

(d) The school under trial had a mascot, a monkey named Scopes.

(e) Christian fundamentalism and evangelicalism experienced a decline in activity in the two decades following the Scopes Trial.

Keep reading to see the answers.

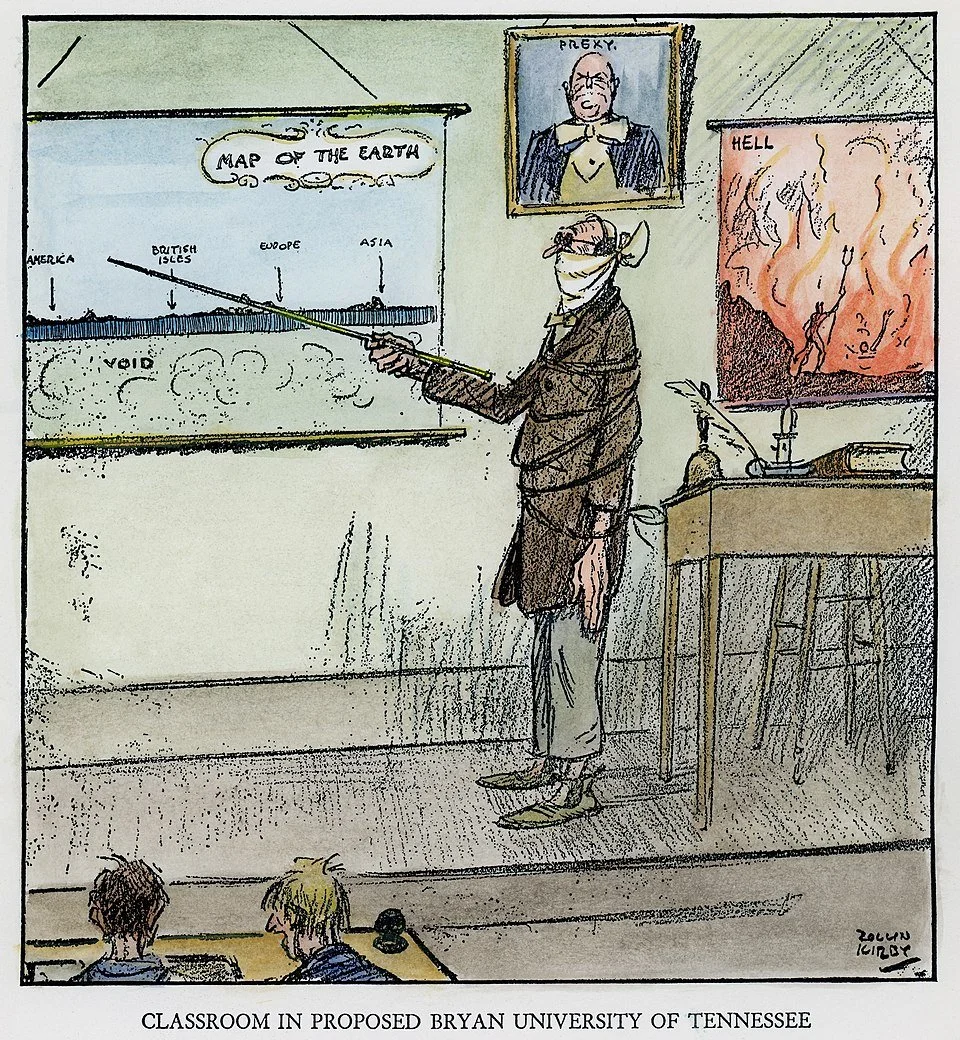

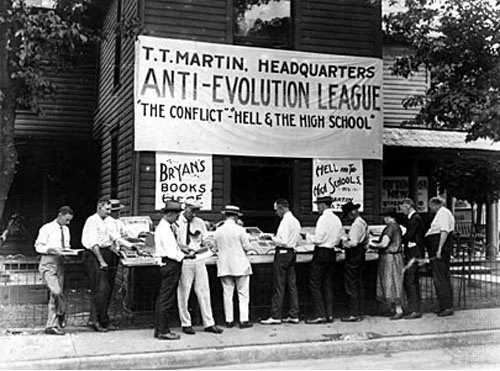

Another example was the highly watched 1925 Scopes Trial (State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes) in the Criminal Court of Tennessee in which a public school teacher was prosecuted for teaching about evolution at a time and place when only creationism was allowed. This conflict between Christianity and science was not new—as previous described, the second wave of revivalism during the Common Schools Era was partly a response to the American Enlightenment and its elevating of science and technology; and a century later, this conflict would arise again in response to the Cold War and related technonationalism. Yet, what was new was the opposition to teaching evolution.[38] Widespread organized efforts to ban such instruction did not begin until the 1920s when the emerging Christian Fundamentalist Movement embarked on a state-by-state campaign to legislate such a restriction, succeeding in three states (including Tennessee). As will be repeated half a century later with anti-abortion campaigns, it was not the case that pre-existing widespread opposition was what galvanized Christian activism, but rather the opposite, that Christian leaders strategically selected a topic and generated a moral panic that would prove effective at mobilizing the public to act.

Image #1: “Classroom in Proposed Bryan University of Tennessee” (cartoon critical of Bryan and creationism), by Rollin Kirby, 1925 (public domain)

Image #2: Anti-Evolution League at the Scopes Trial, in Literary Digest, 7/25/1925 (Mike Licht, Anti-EvolutionLeague, CC BY 2.0)

Following the Scopes Trial, Christian fundamentalism and evangelicalism declined in public visibility (primarily because of the passing of its most prominent leader, the prosecutor of the trial, William Jennings Bryan, and because of the thriving of the Social Gospel Movement), but evangelicalism in particular reenergized and shifted Rightward in 1947 when the National Association of Evangelicals formed. Fundamentalism and evangelicalism had been considered on the fringe, but the Association took the lead in giving it more intellectual credibility, more openness and flexibility across traditions, more organizational infrastructure, and more visibility. What followed was exponential growth, starting in the Southern United States, where its paradoxical evolution was filled, on the one hand, with democratizing potential (by giving some space for more agency among Black people and women, even if only temporarily), and on the other, with increasing regression (by consolidating power and authority in White men).[39]

This growth coincided with the mainstreaming of some of the central tenets of evangelicalism, including an emphasis on individual salvation and not on structural or systemic reforms. In this view, racial and class disparities may exist, but only because we all have strayed from Christian ethics, including in our governments (with the separation of church and state), our families (with diversifying norms of gender and sexuality), and of course, our schools, which are not merely less Christian than they should be but have actually become anti-Christian, and in so doing, are what are causing inequity, injustice, moral decay, and so on. The evangelical resurgence, its theme of being persecuted, and the imperative of spiritual warfare would help to lay the groundwork for the most significant shift in organized Christianity in U.S. history during the four decades to follow, namely, the emergence of the New Christian Right and its intersections with conservative and neoliberal ideological and political formations.

—-

[27] For more on the history of early public school systems, see Tyack, D. B. (1974). The one best system: A history of American urban education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kumashiro, K. K. (2020). Surrendered: Why progressives are losing the biggest battles in education. New York: Teachers College Press.

[28] Blount (2005). Tyack (1974).

[29] For more on Reconstruction and religion, see Butler, A. (2024). White evangelical racism: The politics of morality in America. 2nd Ed. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. Sinha, M. (2024). The rise and fall of the second American republic: Reconstruction, 1860-1920. New York: Liveright.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Kosar, K. (2015, September 23). Kill the Department of Ed? It’s been done. Politico. https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2015/09/department-of-education-history-000235.

[32] See Butler (2024). Sinha (2024).

[33] For more on lynching and Jim Crow, see Horne, W. (2024, October 17). What Christian Nationalism looked like in practice. Time. https://time.com/7026778/christian-nationalism-jim-crow.

[34] For more on schooling in Hawai‘i in the early 20th century, see Taira, D. (n.d.). Americanization through the School System. Imua, Me Ka Hopo Ole. https://coe.hawaii.edu/territorial-history-of-schools/americanization-through-the-school-system. Morgan, M. (2014). Americanizing the teachers: Identity, citizenship, and the teaching corps in Hawai‘i, 1900-1941. Western Historical Quarterly, 45(2), 147-167. Tamura, E. (1993). Americanization, acculturation, and ethnic identity: The Nisei generation in Hawaii. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

[35] For more on the emerging theologies post-Civil War and their impact on education, see Apple (2001).

[36] Ibid.

[37] Lugg, C. A. (2001). The Christian Right: A cultivated collection of interest groups. Educational Policy, 15(1), 41-57.

[38] For more on teaching evolution, see Apple (2001).

[39] For more on the resurgence of evangelicalism, see Apple (2001).

Return to Table of Contents | Proceed to Part IV